In Search of the Elusive Humpback

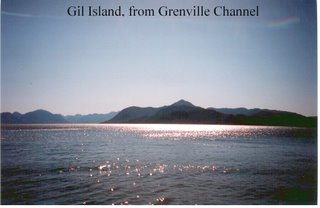

On the southern tip of Gil Island, a short boat ride from where the Queen of the North sank earlier this year near Hartley Bay, there exists a whale research station operated year-round by Hermann Meuter and Janie Wray. Alumni of Paul Spong’s Orcalab on Hanson Island, Hermann and Janie have been researching cetaceans, principally humpbacks and killer whales, full-time since 2002. This September I spent a fascinating week as their guests, getting to know the area, going out on the water just about every day, and helping to record whale songs from their acoustics lab.

In the course of my very enjoyable stay, I was lucky to see several humpbacks and a few killer whales, plus two colonies of Steller sea lions, an elephant seal, and numerous Dall’s porpoises. And while I did not see the fabled Spirit Bear which roams nearby Princess Royal Island, other visitors to the region did. Nor did I see any wolves. But, what I did was many of the 64,000 returning pink salmon which returned to Gil Stream this year to spawn. I watched in utter amazement as the females desperately sought to lay their eggs in the stream bed, before breathing their last breath, as Janie patiently filmed the scene from the shore. Unfortunately, the number of pinks returning to other rivers and creeks in the region is way down this year.

This is normally a good time of year for spotting and recording humpbacks in the area, as they bulk up on their way back down to Hawaii after a summer of feeding in more northerly climes. Of the estimated 20,000 humpbacks worldwide, roughly 5000 make the Northeast Pacific their summer residence. Of these, approximately 200 frequent the waters around Gil Island, including the appropriately-named Whale Channel, Squally Channel and Wright Sound. This fall, however, the bulk of the local population seems to have gone to some of the more inner channels, such as Ursula and Douglas, where Janie discovered more than a dozen individuals in recent days.

Cetacealab’s three sets of solar-powered hydrophones continuously monitor the sounds of the orcas and humpbacks – from Money Point in Wright Sound, Borde Island in Whale Channel, and just in front of Cetacealab in Taylor Bight. Hermann and Janie have a five-year record of the presence of these whales in the area – where they are, the kind of activity they are engaged in, what pod they are from, and their abundance. The value of their work is therefore incalculable; no one else is doing anything as remotely ambitious in such an out-of-the way, pristine though hostile environment.

Hermann and Janie eat, breath and sleep whales. Loudspeakers are wired throughout their cabin, which includes the acoustics studio and their living quarters. Thus, if the whales start singing during the night, the sound will undoubtedly wake the intrepid researchers, prompting them to get out of bed and run down to record them. There is even a loudspeaker outside their cabin, just in case they are not in the house when the singing begins.

Meuter and Wray also spend as much time as they can out on the water, looking out for the whales, and observing their behaviour up close and personal, as it were. In the summer, when the weather is good, they are out almost every day; in winter, they are lucky to get out one week in three. The rest of the time, they just tough it out in the comfort of their cabin cum research station, compiling statistics, catching up on paperwork, applying for research grants, etc.

Currently, there are two looming threats to the whales of the area, as well as to Cetacealab’s research program. One is a project called Batholiths, which, if approved, will entail three weeks of continuous seismic booms in and around Douglas Channel in the fall of 2007. The other is Enbridge’s Gateway pipeline and Kitimat tanker terminal proposal which, if it gets the green light, could see supertankers regularly transiting Wright Sound, Squally Channel and Whale Channel with their cargo of Alberta crude oil by 2010. Both of these projects pose significant risk to the health and existence of the whales, whether from the interference they will cause to their echolocation and feeding habits, or, in the case of the Enbridge project, from the oil spill threat.

If you would like to learn more about Cetacealab and the whales of Caamano Sound, and are concerned about the fate of the whales in light of the impending projects, visit the lab’s web site at www.cetacealab.org. Cetacealab is also a registered charity in British Columbia, which means that all donations are tax-deductible. Hermann and Janie heavily rely on public donations to pay for equipment, maintain the lab, and sustain their unique research program.